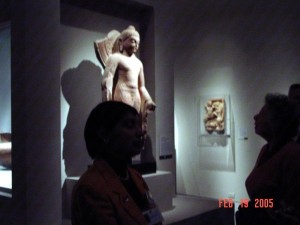

STANDING BUDDHA

Researched by Rochelle Almeida

1979.6

Artist: Unknown

Pink Sandstone Sculpture

Indian (Mathura, Uttar Pradesh)

Gupta Period, 5th century.

Who is depicted in this sculpture?

This sculpture depicts Prince Siddhartha Gautama, better known to the world as The Buddha which in Sanskrit, the ancient classical language of the Indian sub-continent, means The Enlightened One.

Who was the Buddha?

The Buddha was born Prince Siddhartha in an ancient royal family, now a part of the territory of the kingdom of Nepal. He lived from 563 to 483 BC, i.e. for 80 years.

What do we know about the background of The Buddha?

We know that his mother Maya became miraculously pregnant in the Garden of Lumbini in present-day Nepal. He was also born miraculously because he emerged out of her side instead of like normal babies. He was a prince and enjoyed a royal privileged lifestyle. He was married and had a child. Being sheltered since the time of his birth, he had no notion of human suffering or want and, as an adult, he was exposed for the first time to a sick man, an old man and a dead man. This exposure made him aware of the existence of sickness, age and ultimately death. This realization prompted him to leave the palace and attempt to find an end to such suffering. He became an ascetic himself, leaving the palace quietly in the dead of night.

For the next six years, he tried to find an end to human anguish. He ate only 6 grains of rice a day and became completely emaciated. It was then that he realized that neither wealth nor poverty was the way to Enlightenment, but the Middle Way. Finally, he sat under the Bodhi (Fig) tree to meditate. Then, Mara, the God of Death grew nervous because Siddhartha was getting too close to escaping Death and so Mara sent out three temptations to lure the Buddha away—Ignorance, Lust or Passion and Fear. But Siddhartha remained immune. He reached his hands downwards to touch the earth to signify that he had attained Nirvana or had reached Enlightenment. He was 35 years old when he reached Enlightenment and preached his first sermon in Deer Park. He lived for 45 years more, performing miracles and preaching his new message of brotherhood of all men and ahimsa or non-violence towards all living beings.

He is said to have eaten either tainted pork or mushrooms, contracted food poisoning and died. His remains were cremated and were placed in stupas (Buddhist temples) all over. The statue of the Reclining Buddha that is seen in many stupas all over the world is a representation of the Buddha on his deathbed.

Of what material is this statue made?

This statue is made of mottled pink (sometimes referred to as red) sandstone which is plentifully quarried all over the northern Indian sub-continent. It was carefully hand sculpted.

When was this statue sculpted?

This was probably made in the 5th century A.D. when the spread of Buddhism all over the Indian sub-continent was substantial and when pink sandstone panels depicting the life of the Buddha and statues attesting to his divinity were made to spread the faith. This red or pink sandstone sculpture had a great impact both historically and artistically, marking the first figural representation of the Buddha.

Why was such sculpture made?

It was apparently developed as a means of preserving Buddhism, then the foremost religion in Central Asia, from the onslaught of two religions—Hinduism and the then new faith, Christianity. The story of the Buddha in stone sculpture made Buddhism more romantic and more accessible to people who were faced with the representational gods of Hinduism—Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu and the compelling figures of Jesus on the Cross and the Virgin Mary which, in art form, could grip their imagination.

What is Gupta Art?

The Gupta Period (early fourth to early sixth century), often referred to as India’s Golden Age, left the indelible print of India’s culture on the civilization of its neighbors and established an apogee against which later Indian dynasties measured their accomplishments. Cultural achievements reached unsurpassed heights, literature and the arts and sciences flourished under lavish imperial patronage. Reflecting the new rationalism and humanism that permeated all aspects of Gupta culture, art forms and style developed that provided the prototypes for areas quite distant from the subcontinent.

In sculpture, the period fostered a new naturalism as well as a harmonious ordering of a new vocabulary of forms. The highly refined system of aesthetics produced softer, gentler curves, fluid transitions from volume to volume and a sustained and complete harmony of smoothly flowing forms. Disciplined by a strict geometric rationalization in the fifth century, this system evolved into one of humanity’s greatest art styles—the classic Gupta style.

What are some of the significant aspects of this statue?

This statue exudes monumentality. This is a representation of the Shakyamuni Buddha, i.e. the Sage of the Shakya clan because Siddhartha was a member of the Shakya clan. Images of the Buddha were not created until 500 years after the Shakya dynasty and so nobody really knows exactly what the Buddha looked like.

Why then is the Buddha usually depicted in a very stylized way all over the world?

The Buddha was said to have been born with 32 major and 80 minor signs to show that he was a Universal Being. Some were a result of his royal birth, others were acquired through his lifetime. For example, there is the bump at the top of his head (Ush Nisha) that shows his expanded wisdom—his Enlightenment, which made him smarter than anyone else. Again, when he chopped off his hair, it automatically formed snail-like curls around his head. Hence, the Buddha is also depicted with this typical coiffeur. Also, he has a round dot on his forehead which also signifies his omniscient wisdom. His elongated ear-lobes are a result of the fact that, according to legend, when he gave up his royal lifestyle to become an ascetic, he removed his heavy gold ear-rings which left his ear-lobes extended. Furthermore, the Buddha is usually depicted with webbed finger and toes (neither or which are visible on this statue as it has suffered considerable damage). These signify the fact that he scooped people up before they fell as a result of their bad deeds. Images of the Buddha were shipped all over the eastern world to spread the faith and the webbed fingers and toes tended to travel better (they remained intact) than those statues that had individual fingers and toes.

What other aspects of this statue should we note particularly?

Every features of this statue is indicative of the Buddha’s divinity. The anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha developed during the reign of King Kanishka, the most famous of the Kushans at the end of the first century A.D. or the beginning of the second century and was destined to sweep the entire Eastern world.

The Buddha’s serene face is composed of full-rounded volumes (what is sometimes referred to as the Mathura pudginess) and smoothly interlocked shapes that from a skillfully balanced totality. Its fulsome appearance, with rounded cheeks, fleshy lips, almond-shaped eyes and high, gracefully arched eyebrows, is heightened by the potent curve of the loop of the upper hem of the garment below the neck.

He has eyebrows that are shaped like archers’ bows. His eyeballs are sculpted in the shape of lotuses or water-lilies, the national flower of India. His nose is shaped like a parrot’s beak. His lips are like ripe fruit, his chin is in the form of a mango. The three lines around his neck imitate the shape of a conch shell, used in a lot of Indian sacred rituals. His upper torso is made to look like the head of a cow, an animal sacred to Hinduism.

What about his clothes and accessories?

The Buddha, like all monks, is depicted as wearing two robes—an undergarment tied with strings which is sculpted so elegantly that the artist has made stone appear to have transparency, and an over garment.

The Buddha had a huge halo around his head (to signify his holiness) of which only a tiny part remains. Right behind his ears are sculpted the petals of a lotus, a flower that

blooms beautifully in the muck—signifying the fact that even out of the muck can emerge beauty. Thus, from out of the muck of life, one can still get a Buddha.

The Buddha is also presented bare footed because he traveled everywhere on foot after he left his father’s palace, never once riding a horse again. Hence, even today, all over the world, Buddhist monks travel from place to place on foot.

What do his hand gestures signify?

Both wrists on this statue had been destroyed, but the right hand was sculpted to be held upwards in the gesture signifying Abhaya Mudra which means Fear Not. The left hand would have reached downwards, signifying the gesture of gift-giving. Thus, this figure of the Buddha reassures and rewards the believer.

What else can we state about the iconography of the Buddha statues?

The iconography of the Buddha as a Graeco-Roman figure started in the ancient city of Taxila in present-day Pakistan and spread to Mathura, the southern capital of the Kushans, where it became more Indianized. As the pilgrims took this new figural art eastward from Mathura, the images changed. No longer Graeco-Roman, no longer Indian, these sculptures adopted both the dress and physiognomy of Burma, China, Southeast Asia and eventually Japan. Thus, the revolutionary Graeco-Buddhist sculpture of Gandhara became the accepted art form of the entire Buddhist world.

Some historians believe that Gandharan art (of which this statue is a fine example) came about through the descendants of Greek artisans and sculptors brought to the Greek satrapies or colonial territories by Alexander the Great around 327-326 BC. These made their way into Gandhara where they carved the figures, especially in the area of Taxila where the art was basically Graeco-Roman.

Conclusion:

This then is the great contribution of Gandharan art under the Kushans; the development of the Buddha image, an art form that must be considered one of the important in the history of Asia.

Bibliography:

Orzac, Bebe Fleiss and Edward S: “Gandharan Art of Central Asia”. Arts of Asia. January-February 1983, 78-88.

Selig, Catherine: “Art of South and South East Asia”. From class notes taken during lecture delivered to Highlights Trainees in the Galleries on February 26, 2001.

Continue the tour of the Asian Galleries to enter The Ming Scholar’s Garden of the Astor Court