Bombay seemed to sparkle softly in the clear light of a winter’s afternoon when I arrived there in late December 2007 at the start of what would prove to be one of the most exciting months in my memory. Brisk temperatures and a complete lack of humidity peeled away the polluted haze that usually accompanies the weary traveler on a ride into the city from the distant suburb of Andheri where the international airport is located. Habitual traffic snarls along the Western suburbs undid the speed acquired on the newly-minted flyovers of which the city is proud, but by the time we arrived at the waterfront at Apollo Bunder to occupy rooms at the Taj Mahal Hotel, we were well and truly ready to crash.

We lay bathed in golden light at dawn as the sun swept over the Arabian Sea and gilded the granite edifice of the Gateway of India (right). In the hushed air-conditioned seclusion of our room, we floated miles away from the urban chaos. Later, fuelled by an incredible breakfast buffet, we strolled outside the Taj amidst the rubble left behind by cable installation on the tarred roads as eager vendors attempted, somewhat inexplicably, to sell us colossal balloons. At the Wellington Fountain, near the Regal Cinema, traffic moved far more smoothly than I remembered. Our forays into the National Gallery of Contemporary Art in the former C.J. Hall permitted us to admire the architectural handiwork of Rohit Khosla of Delhi who has transformed the Victorian space quite ingeniously into a modern art gallery featuring the work of India’s most significant living artists.

Fort Area on Foot:

But it was on a walking tour of the former colonial area of Fort that I fell on love all over again with the city of my birth. Armed with Fiona Fernandez’ book entitled, Ten Heritage Walks of Mumbai, I embarked on my round of re-discovery, starting at the fabulous Indo-Saracenic Prince of Wales Museum guarded by palm tree sentinels. Crossing the street to the quadrangle of Elphinstone College, my own proud alma mater, my heart skipped a beat as memories of carefree college-days came flooding back. Having been recognized as a heritage building, it has been spruced up considerably and looks far more spiffy that I can ever remember it being during my own dust-ridden student years within its hallowed walls. Still, the fact that the college counts among its alumni some of the city’s best-known industrialists, patriots, lawyers and statesmen is reason enough to excuse the lack of routine maintenance.

Walking over past the Civil Courts towards the outer borderlines of the campus of Bombay University, I admired the Indo-Gothic facades, the spiral stairways, the tall pillar of the Rajabai Tower within whose walls lie concealed the library with its miles of stacks over which I had once poured as a doctoral student and the handsome columns of the Convocation Hall where once, in graduation cap and gown, I had been part of the procession that comprised Commencement Exercises . This time round, I proudly posed with Llew (see above), delighted to introduce him to the oft-frequented pathways of my happy youth.

The Bombay High Court and the Central Telegraph Office that lie along the periphery of the Oval Maidan echo architectural elements and bring the walker to the famous Flora Fountain, the heart of the old Fort. All along the road leading eventually to the embrace of the Old Lady of Bori Bunder, the Victoria Terminus (above left), the eye is thrilled by the variations in architectural design of India that characterize the buildings of the late nineteenth century. It is difficult, however, to truly admire their details as one is too busy watching one’s step to avoid tripping over pot holes and recently dug up sidewalks. Still, the adventurous local historian in me could not but be swept by a sense of exhilaration as I traversed those stony pathways, taking at will a by lane here or an alley there only to find myself in a Victorian park or abreast of a perfect crescent or gazing upon the walls of a Parsi agiary at one step and the solid masculinity of the old Reserve Bank of India where I had once worked or the Neo-Classical columns of the Town Hall (below right) on the other. I cannot recommend enough that visitors to Bombay abandon the indignities of public transport to traverse randomly on foot over these historic colonial realms.

Bombay on Wheels:

Bombay also promises the soft breezes of the Arabian Sea at Marine Drive where the Art Deco buildings imitate those of Miami’s South Beach. Alongside the gigantic concrete ‘tetrapods’, built to combat the fury of the ocean’s crashing waves, these buildings form the jewels in the Queens Necklace that glitter at night as endless traffic snakes its way up into the wooded reaches of Malabar Hill. It is worth exploring this part of downtown Bombay from the well-brushed sands of Chowpatty Beach, site of once-significant protests against crippling colonial policies, to the leafy serenity of Laburnum Road at Gowalia Tank, site of Mani Bhavan, a grand and lovely wooden mansion where Mahatma Gandhi made his home during his infrequent visits to the city. Converted quite movingly into a Gandhi Museum, this is one of my favorite museums in the world, modest though it might appear to the well-traveled visitor. The vignettes from Gandhi’s life, captured on the top floor in miniature are superbly done and the simple room, cordoned off to visitors, in which Gandhi spent his time, furnished only with his meager possessions– low desk, sandals, walking stick, eye glasses, etc. is deeply moving, particularly to those who are well-informed about the policies and personal beliefs of the Mahatma, his austerity and his renunciation of all comforts and luxuries.

On Malabar Hill, the Parsee Tower of Silence, last resting place of the religion’s devotees, which cannot be visited but merely skirted, brings visitors a lesson on the unique beliefs and practices of this tiny but very significant Indian ethnic minority who have contributed so enormously to the cultural and economic life of the community. It is also on Malabar Hill that a Jain Temple is an oft-visited site–its marble carvings and sterling silver doors fascinate the first-time visitor. Atop a resevoir that provides the city with its water supply, sits a revered garden whose curiosities include an Old Lady’s Shoe (from the Mother Goose Rhyme) and a Floral Clock. These were the sites I visited often as a child on a weekend evening’s outing in the company of my parents and brothers and visiting them today always brings a lump of nostalgia to my throat.

Further down the tree-lined street, where the Peddar Road Flyover emerges, take a detour towards the left to drive along Warden Road to see the apartments that comprise some of the world’s most exorbitant real estate. At the end of this road, at Haji Ali, stands a Muslim mausoleum in the middle of the sea, its marble façade lapped gently by the grey and murky waves that engulf its walkway completely at high tide. The drive along the city’s Golf Club and Turf Club take one into its greener reaches to bring into focus the world’s largest outdoor laundromat at Mahalaxmi Railway Station where the city’washermen or ‘dhobis’ launder the clothes and linens of the populace in a completely unique fashion.

Carven Craftsmanship in Elephanta’s Caves:

Amazingly, only a short boat ride away from the Gateway of India, at Elephanta Island, are perfectly preserved Hindu rock-cut monolithic cave temples, a trip to which offers two things: an unusual view of the city from the Bay in noisy ‘launches’ that imitate the voyages of British administrators to and from the colony, and the opportunity to marvel at the industry and artistry of devoted carvers who created exquisite religious panels between the fifth and seventh centuries to appease their vast pantheon of gods.

Of these, Shiva as Trimurti (right) is the best known but every single one of the panels tells its own quiet story—reams of Hindu mythology are faithfully reproduced upon their granite walls as also the long saga of wanton destruction perpetrated upon these temples by fanatic Portuguese missionaries in their zeal to spread the Christian faith in newly-colonized India.

As a bonus, one can find humor and comedic performances in the antics of brazen monkeys, one of whom actually snatched a bottle of Limca from a startled tourist, twisted the screw top open and drank thirstily off its contents, right before my disbelieving eyes.

Named by the Portuguese for a stone elephant that once guarded entry on to the island, there is now a modern mini-railway line (left) that takes visitors from the boat’s dock to the rock-hewn steps—lined by the distractions of stalls selling clothing, jewelry and cheap handicrafts—where palanquins hoisted up by sturdy bearers allow one to be transported in comfort.

‘Mumbai’ in Motion:

Recently re-named ‘Mumbai’, the city, like the country, is obviously in motion. It has often been described in guidebooks as India’s most prosperous city and indeed this is evident in the many gold and diamond jewelry ‘showrooms’, gourmet restaurants and vibrant nightclubs that have sprouted in recent years to fulfill the desires of the nouveau riche. But there is the other Bombay—the Bombay that is dearer to my heart—a Bombay of gracious old buildings whose paint is peeling hopelessly away and stripping it of its collective memory in the bargain. A Bombay of timeless peanut-vendors and juice-pressers who tempt local residents with small treats on a routine day. A Bombay of wily urchins and crafty salesmen, stoic policemen and crude taxi-drivers, of jaded long-distance commuters and street side booksellers. This is the Bombay that continues to survive in the midst of the flashy new money, the current awareness of heritage preservation, the celebrity chefs whose TV programs are raking them millions of rupees in multi-cuisine restaurants and the number-crunchers on the Bombay Stock Exchange, where fortunes are made each passing day as the Sensex index rises. This is not the Bombay of my growing years, but its newly-fashioned global avatar.

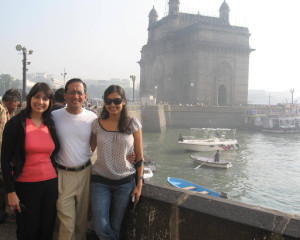

Who would ever fathom that in this seething city of eighteen million people, we would actually bump into friends, also visiting India from the United States and Australia, at Bombay’s most distinguishable monument The Gateway of India (left)? Amidst hugs and squeals, we posed for pictures taken by an obliging passer-by, and remembered our salad days in this nostalgia-ridden city (see picture above left).

Indeed, much has changed and though I travel to the city if not twice then at least once a year, I am still unable to keep abreast of its rapid alteration. But no matter how changed its complexion, the eternal heartbeat of Bombay is what I carry with me in my consciousness wherever I may travel or choose to live.

This is the Bombay that I invite you to discover for yourself on your own adventurers in the city.

(To continue your journey with us through the route we took in January 2008, please click on the Goa link).

Bon Voyage!