The disappointment of not seeing tigers was dissipated by our arrival in stirring Chittorgarh, a part of Rajasthan that I had never before visited. Here, the main attraction is the incredible fort that stretches out as far as the eye can see along a rocky promontory reached along a snaking mountain path that opens up at seven intervals through ‘Pols’ or Gates, each of which is studded with metal goads to deter charging elephants. Merely imagining the warfare that might have smeared the walls with the blood of courageous soldiers, kept me deeply reflective during the long drive up to the fort’s ramparts.

Once the driver expertly negotiated those narrow gates and entered the fort’s expanse, there was so much to discover. As Rajasthan’s mightiest fort, it had been the target of successive invaders from 1303 when Sultan Allaudin Khilji had marched his troops in, to 1535 when Bahadur Shah of Gujarat had made a bid for the territory, to the final assault upon it by mighty Moghul Emperor Akbar who in 1567 was finally able to capture it and vanquish the brave Rajput rulers.

In a brilliant sound and light show that we witnessed along the walls and ramparts of the fort, we heard the stirring stories of ‘jawhar’, a conspiracy to commit mass-suicide by the honorable women of the court, by jumping into a bonfire, because they would rather give up their lives than be violated by the marauders. I could not help wondering why these women did not choose a more painless way to die—but then, where would be the sting of Death in so pyrrhic a sacrifice?

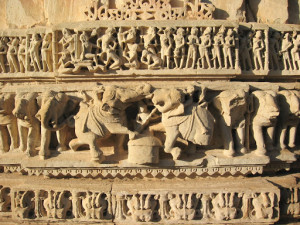

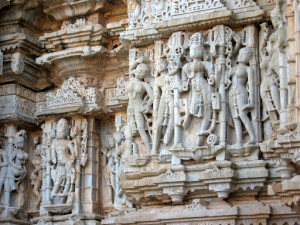

Chittorgarh is too massive to discover on one afternoon or indeed even in a month. Its many corners are studded with Hindu temples, one of which honors the royal lady Meera Bai, a poetess and spiritualist and great devoteee of Lord Krishna whose poems and songs are the stuff of legend inasmuch as the tales of courtly heroism and chivalry hark back to a long-dead epoch. The most visited of monuments in this complex is the Vijay Stambh or Victory Tower (left), a monument that rises nine stories into the sky and features an intricate array of carved figures. Just a few feet away is the breathtaking Kalika Mata Temple, also covered with stone carvings featuring a stunning array of fat and lovable elephants and Indian deities portrayed as courtesans in various poses of dance and seductive entertainment (see below). When I had encircled the temple and paid respects inside to the goddess to whom it is dedicated, I made my way down to the Gaumukh Resevoir, source of a natural spring, named for Nandi, the Bull or ‘Gau’ whose sculpture guards the entrance.

Another attraction at this complex is Padmini’s Palace, a small and rather modest two-story structure in white marble (below right) that commemorates the chastity and honor of Queen Padmini upon whom Allaudin Khilji had lustful designs. Because her husband, the Rajput chieftain, would not give her up to the more powerful Khilji, she devised a way by which she could be seen by him indirectly–through a mirror hung on a wall—thus preserving her modesty and her honor. Such tales of men and women who went to their deaths painted with the bright colors of honor and nobility abound in stirring Chittorgarh, a town that is visited only on the daytrip circuit by tourists from nearby Udaipur.

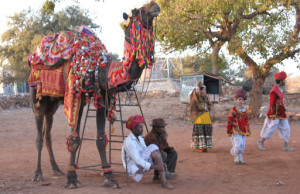

Perhaps that would explain why its people seem to be untouched by the swift march of time. I met the cutest children selling postcards who completely stole my heart away long before their bright and dazzling smiles reached out to me in wordless ways and their total lack of guile pulled at my heart strings. Of these, I will never forget 12 year old Udailal, from whom I purchased postcards and who persuaded me to request members of our party to buy postcards from him. A Grade VIII student during the week, he sells postcards for pocket money on the weekends. His industry and his enterprise were admirable in one so young and so determined to make a success of his life. In his spotless blue shirt, perfectly pressed and in the neatness with which his hair was oiled and combed, I saw a level of grooming that proclaimed high self-esteem and I felt transported to the fifties, to a time when kids were completely mannerly and lovable and a true pleasure to talk to. The future of India, I realized, lies in the hands of these children and if their fortitude and hard work and sense of dignity that comes from such simple labor is any indication, I am convinced that only bright days lie ahead for the country of my birth. It was brushes with such ordinary folks as these that made me realize how essential it is for the sensitive traveler to look beyond the beggars and the crippled in order to find positive signals of the strides that India has recently made and to know that this trend can only continue into the future.

Another fleeting moment that stays with me in Chittorgarh was the naked gratitude I spied upon the face of our tour guide when I offered him a cup of coffee during one of our tea breaks. “Here”, I said to him, completely spontaneously, “why don’t you have this? I think you require this much more than I do”. He looked at me as a smile of unabashed delight spread all over his face while he reached out and took the proffered cup from my hands. I know that it is sights like these that will stay with me long after I have filed away the photographs of temples and forts and mosques and palaces.

Back on the Palace on Wheels, the twinkling lights on the fortress of Chittorgarh receded into the distance as the train slowly ate up the miles towards Udaipur, stately residence of kings and their consorts.

(To continues your travels with us on the Palace on Wheels, please click on the Udaipur link).

Bon Voyage!